Maura Coughlin (Bryant University) Elodie La Villette: The Bas-Fort Path at Low Tide, Dieppe for OBJECT LESSONS at ASLE, August 2021.

Brittany: Images, Things and Places

material and visual culture in Brittany, the Atlantic coast of France and farther afield

Sunday, September 19, 2021

Monday, November 2, 2020

Podcast and video...

Update: Our first reviews!

Gillen D’Arcy Wood in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (NCAW)

and Rebecca Bedell in ISLE.

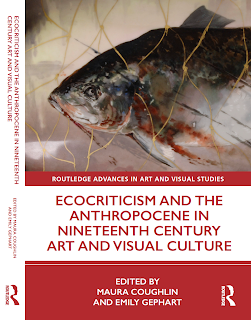

My university is featuring video and podcast versions interview with me (with Sam Simas, production by Jonathan Fonseca), discussing the book (Routledge, 2019) I co-edited with Emily Gephart (Tufts University), Ecocriticism and the Anthropocene in Nineteenth-century Art and Visual Culture.

Friday, April 17, 2020

Danse Macabre

An in-conversation with art historian Maura Coughlin and artists Kahn & Selesnick exploring the series of art historical references that have influenced their work.

Friday, March 20, 2020

Cecile Borne: Tideline Gleaner (part one)

Cécile Borne finds her subject matter and materials on the tide line. She is a multi media artist based in Douarnenez, Brittany. Like the gleaner who was so often painted or photographed picking the remains of a wreck, gathering mussels, kelp or flint stones on the French North Atlantic shores, she finds her materials on the intertidal zone. But unlike seaweed that has been gathered from these beaches for centuries, this fabric is unmoored, never having had a holdfast—an alien resident of the water, not bound to a zone, but subject to the tides and wind. She calls her self a plasticienne chiffonnière: a rag sculptor.

Douarnenez is a port town of many contrasts, from its past as both an industrial fish cannery and an artist colony, to its present as a town of artists and summer visitors in the aftermath of fishing. In installations of the past several years, materials gathered on the strand assume new forms. As part of her practice, she walks the Bay of Douarnenez, searching out unlikely material: textiles that the sea has thrown back on the land. This stretch of coastline was the site of her adolescence—it is a place intimately known. When collecting in the summer, she often swims or dances on the strand. This is a fully embodied practice-- hardly a coincidence as Bourne studied contemporary dance in London and Paris. Her practices of walking, salvaging, recuperation and installation are all bound together in an ecological immersion in place.

Inlets or criques along this bay each have their own particular beach—one made of round stones, the next sand and slate fragments, another flat strand. Many small streams course down through villages, farmland and woodland to the sand, mixing fresh with sea water. Favorite criques are those that best trap old cloth. Some textile bits were old-fashioned sardine boat sails that have been in the sea for years, others are fragmentary, waxed garments formerly worn by fishermen or sailors. Occasionally she finds pieces of household linens or even costumes discarded after Mardi Gras. Other textiles are hard to identify: some were used as rags on boats and then discarded. Some are just lost or slip overboard. The sand often buries things that come ashore; when they spend time under it, they are marked by its minerals and organic matter. These imprinted fragments are later found only by attentiveness to the smallest visible edges. Although the Bay of Douarnenez opens to the Iroise, the North Atlantic and, of course, to the global ocean, most of the textiles that wash up have local origins (such as rags that bear the mark of a hospital laundry service in nearby Vannes).

|

| walking the bay |

|

| Mixed seaweed and debris on the wrack line |

So much human generated debris is snared, reeled in or caught in the rocks and tide pools, or buried in the sand above the tide—scattered in pebbles, entangled in dried kelp. Few people notice the amount of textile waste on the beach. Often it has taken on the color of sand and, like plastic, it breaks down into ever smaller parts.

|

| Material gleaned from one walk |

|

| Dentelles, or sea-lace |

Borne collects, rinses, and orders her marine fabrics. Her studio serves as an archive, storehouse or sorting zone for her recuperated, and potentially restored finds. This is not exactly a process of recycling—rather it is a form of forensic restitution that permits the material to tell stories of the bodies that once wore it.

|

| a fragment of waxed clothing |

A black piece of fabric, when held up to the light, has ripples etched into it: she says that the sea often leaves marks of its movement. She tells me stories she has gleaned from her finds: over the course of a few winters of walking the bay, she gradually reassembled a 12-piece set of damask table napkins. All had the same pattern in the weave, yet were marked very differently by the sea, who acted on them, while submerged, like a master printmaker. She had not found any others at all like this: they must have come from the same source. She speculates that this singular set-- perhaps no longer new-- might have been passed down in the family of a fisherman who used them as rags on his boat and, one by one, they were thrown or fell into the sea, and made their way to shore all along the bay. A shirt with a pattern of sailboats was torn in half, used for some dirty job, then discarded. The two pieces washed up in utterly different sites, and, as unlikely as it might be, Borne found them and made them almost whole. A garment with no value in the world becomes an uncanny found object; its two halves utterly marked by their separation and remaking in the sea.

|

| reunited pieces of a long-separated shirt, printed with sail boat pattern. |

Her forensic research opens up untold narratives: finding the name of a child in a raincoat revealed an entire family history: triangulating the coat size (8 years), she determined that it had been in the sea for about 4 years. In reconstructing its story, she was led back, almost impossibly, to a psychoanalyst who had been one of her patrons. In another exceptional find, a stained Tyvek suit (likely discarded after Mardi Gras in Douarnenez) bore the name “LATEUSE.” When googled, its former owner was revealed to be a boastful local man who liked fast cars. Borne took apart the suit, stretching pieces that bore the imprint of his buttocks, knees and elbows. They became uncanny prints, a sort of Veronica veil or true icon of his body.

|

| "Mu(e)s" installed in Saint-Merry, 2014. |

|

| "Mu(e)s" installed in Saint-Merry, 2014. |

Suspended in mid air, the sea-marked textiles, now clean and stiffened, float as if votive offerings from the sea, relics of past lives, animated in an unfamiliar setting. Many Breton chapels are filled with votive offerings that give thanks for salvation and with cenotaphs that commemorate and mourn the lost at sea.

Interview de Cécile Borne from www.saintmerry.org on Vimeo.

In her exhibition "Vestiaires, cirés-récits" at the Port Musée in Douarnenez in 2015, Borne made found maritime clothing come to life, to speak as a second skin. The cracked surface of the ruined waxed garments were first marked by wear, then by what the sea, the sand and the sun did to them.

There is a powerful sense of mourning and absence in the installation: many of the brown, waxed garments are no longer common. Were they discarded by their owners, or do they speak of drowning? Yellow fishing gear has aged or been stained olive or black. Some pieces, wracked up on rocks, or dug down into sand, became the substrate for algae and crustaceons. As organic matter grew, a once functional garment became abstracted by the agency of the sea.

Her installation of 2016, Disparition, is an homage to migrants lost at sea that took loss and mourning to a much wider scale. The presence of bodies, drowned in desperate attempts to find shelter and safety in Europe, are evoked in casts of torsos that float above collections of archived textiles. Mourning these victims of war and the cruelty of closed borders, the Breton culture of maritime votive objects assumes meaning for the global oceans.

|

| Disparition |

Here the sea definitively becomes a site of mourning. The installation laments the lost at sea, and, by extension, the emptying of the sea of all its vibrant life.

|

| Portrait of Cécile Borne by Nedjma Berder |

Labels:

art,

beachcomber,

brittany,

coastline,

cotton,

douarnenez,

ecology,

gleaning,

installation,

maritime,

textile,

waste,

wrack

Sunday, January 19, 2020

Gleaning the Tideline

Elodie La Villette is an understudied late-nineteenth-century French marine artist who had an exceptional ecological sensibility. Her images of the interstitial world of the coastlines of Brittany and Normandy depict transformations and exchanges between the labour of human maritime communities and the materiality of the landscape in shoreline commons. Using the tools of material ecocriticism and ecofeminism, this article analyses her painted North Atlantic ecologies of the human and more-than-human, and finds affinities between her visual attentiveness and emerging marine ecological sciences in France.

The full essay, "Gleaning the Tideline: Elodie La Villette’s Ecocritical Painting" was published in the journal Dix Neuf in 2019.

The full essay, "Gleaning the Tideline: Elodie La Villette’s Ecocritical Painting" was published in the journal Dix Neuf in 2019.

Gift Boat

Before the chapel of Notre Dame de Perros-Hamon, in the

town of Ploubazlanec, near Paimpol (Brittany), a young boy was photographed by Charles

or Paul Géniaux in about 1900. His seafaring costume of wooden clogs,

a fishermen’s beret and woolen sweater marks him as a mousse, or cabin

boy. He holds a model sailboat and sits on a stone wall that surrounds the

church yard. Unsmilingly, his gaze meets the lens of the camera. His skin has

been browned by the sun, as is clear in the contrast between his face and

collar. Sepia tones articulate the material facts of this composition: the

detail is fine enough to notice the nails in the sole of his wooden clogs, worn

over wool socks. Granite and slate textures of roof and wall are opposed to the

white fabric of the boat’s sail. Wool, canvas, and wood—materials

that went to sea—are set off against the stone of the Breton peninsula and its

culture. The model is not

a toy: it is a votive boat or “ex-voto,” either a material commemoration of a

devotional vow of thanksgiving or a demonstration of faith in future salvation

at sea. There is nothing accidental or spontaneous about the details of this

image: the boy’s dress identifies him as a member of the fishing community, the

boat he holds refers to his vocation at sea, and the chapel behind him is a

ritual site devoted to those lost at sea. This image is my starting point for

thinking about the cultural roles played by religious and commemorative

maritime imagery of the French North Atlantic in greater global ocean ecologies

and visual culture. In 1900, the cash economy of fishing (that this boy

may have already entered into) had been driving transatlantic trade for

centuries. I would like to suggest that the photograph can be read as attesting both to this boy’s entry

into a marketplace of global capital (as a human resource) and as a witness to

a very different sort of economy: the gift economy of memory and commemoration expressed

through the votive object.

The full text of this essay,

“Votive Boats, Ex-votos

and Maritime Memory in Atlantic France”

is forthcoming in Cultures of Memory in the Nineteenth Century: Consuming Commemoration.

Grenier, Katherine Haldane, Mushal, Amanda (Eds., 2020.

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

SALT

|

| Paul Géniaux, Marais Salant, Billiers. Early 20th century, Rennes. |

Silver Salts: Realism and Materiality in a French photograph, c. 1900

Working close to home, Paul Géniaux (1873-1929), photographed a female paludier, or salt-pan worker, in Billiers, on the south coast of Brittany in about 1905. Grayscale contrast has material consequences: we cannot avoid the dirt on her apron or her tough, bare feet on the salted earth. Registered in the image’s silver salts is the difference between the light cotton kerchief on her head and the dark skin of her face, exposed to the same blazing summer sun and wind that crystalizes the salt she skims.

Saliculture is a materially intensive agricultural labor, working with sea, sun and wind, yet it shares qualities with fishing and quarrying to harvest salt, the only rock that we eat. In the marais salants of the French Atlantic coast, trapped ocean water increases in salinity as it is guided through grids of carefully maintained, clay-lined channels to ultimately crystalize into prized fleur de sel. Like the crystals skimmed from the briny pan, Géniaux’s photographic practice was a gathering up of the world around him on silver gelatin dry plates. Although allied with a realist approach to photography rather than nascent French pictorialism, Géniaux photographed a highly selective archive of his native Brittany that inventoried the specificity of locally particular gestures, types and trades. Salt workers and their insular, clannish culture had been mythologized by Honoré Balzac, and had been a staple of travel illustration in the 19th century. Géniaux’s photographs generally echoed established visual tropes of rural labor and locale from travel writing to Salon painting; they were widely reproduced as collographs --a photomechanical fusion of camera and printing press-- in journals and as postcards that were reprinted for several decades.

A brief essay on this photograph appears in French in the exhibition catalog Charles et Paul Géniaux. La photographie, un destin (Rennes, 2019).

Tuesday, February 6, 2018

Hemp and Linen: Material Actors

In the summer of 2012 the innovative ecomuseum in Douarnenez, The Port-Musée/ Musée du Bateau presented an exhibition, Fibres Marines as part of a larger regional theme (Chanvre et Lin/ Hemp and Linen) shared that season across multiple sites: the history and importance of the natural fibers linen and hemp in Brittany’s history and the role of these materials in global maritime history.

For centuries, hemp and linen were grown, processed and finished in Brittany and were the materials from which nets, lines, ropes and sails were made.

|

| Map of linen and hemp areas in 16th to 17th century Brittany. |

|

| Leon Lhermitte, Weaver's Workshop. |

Jane Bennett in Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things has encouraged us to look differently at the relationships of the human and non-human worlds. She writes that she aspires “to articulate a vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans to see how analyses of political events might change if we gave the force of things more due” (viii). Putting these materials at the center of an exhibition, and using representations (photographs, objects, films) as supplementary, contextual evidence shifts the terms of a museum visit. The humble matter itself assumes the agency it had all along in the telling of local history.

|

| Duhamel du Monceau's Enlightenment-era encyclopedia of fishing, Traité général des pesches (1769-82. This image demonstrating the fabrication of nets comes from the first volume (1769) which offers a remarkably detailed inventory of halieutics, or the science of the exploitation of living aquatic resources. The images that follow from this volume also speak to the material actors that enabled the harvesting of ocean fish. |

|

| Denis Diderot, Hemp and Cotton Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Plates vol. I Paris (1762) |

A few years earlier, Diderot's Encyclopedia had also demonstrated the processing of hemp (and cotton).

|

| Hemp Roving (Rouissage du chanvre) Journal Universel Paris, 1860 |

In the Douarnenez show, from hemp plants under grow lights to bales of fragrant raw fibers, the ecological materiality of these fibers was foregrounded.

Viewers had to think about the way that these plants made sea travel and shipping possible. Taking the use of these materials for ropes and ship rigging up into the World Wars of the 20th century, the show concluded pointedly: there is too much plastic in the ocean—much of this comes from plastics used in fishing gear and lightweight boats.

Linen and hemp, finally, were offered as solutions to ocean plastics. In concert with other fibers and composites, they can replace petro-chemical resins in promising ways, such as the light, yet biodegradable boats . This show that made materiality central also opened up the possibility of new, sustainable futures.

|

| Naskapi Canoe, made of composite of bio-materials including linen fibers. |

Little material evidence of the industry remains, apart from the intangible memories of the local people and the former manor houses of the textile merchants. The cloth trade brought economic prosperity to Brittany in the 16th to 17th centuries, especially in Léon diocese. With the evocation of the edict of Nantes in 1685, Louis XIV effectively shut down this trade and destroyed the local economy. The Breton Protestants who made up a mass “brain drain” emigration included many cloth dealers and manufactuers (in Rennes, Nantes and Vitré). But during the prosperous time of the linen trade, (like the earlier competitive building of ever-taller Gothic cathedrals in the Ile-de-France region) seemingly remote, linen-producing Breton interior towns in Finistère built elaborate, multi-structured compounds known as enclos. A few of my photos on this blog attest to these monuments of global trade that today are often misread as local oddities, provincial misunderstandings of renaissance classicism.

More reading:

https://abp.bzh/exposition-a-douarnenez.-fibres-marines.-chanvre-et-lin-hier-et-aujourd-hui-31160

https://www.cairn.info/revue-histoire-et-societes-rurales-2010-2-page-53.htm%5d

https://whatofollow.wordpress.com/2016/10/17/travelling-portion-of-the-flax-road-of-brittany-some-info-2/

https://www.textiletoday.com.bd/extraction-processing-properties-and-use-of-hemp-fiber/

https://www.textiletoday.com.bd/extraction-processing-properties-and-use-of-hemp-fiber/

Monday, August 15, 2016

Disappointing stones

Last week, we were on a two- week trip to Brittany. One afternoon, while installed in Douarnenez, we set out to find the Neolithic covered alley at Lesconil (c. 3500-2000 BCE), just outside of Tréboul.

After parking next to one other car on the edge of a field, we followed a footpath into the woods. Three other people were there before us, taking photos and bantering. After they left, we had it to ourselves for a few moments before more people arrived (it was August).

With a few minutes to reflect, the great granite stones, arranged like a dragon's bones, commanded attention. The historical monuments plaque, nearby, described how this sort of dolmen, a passage tomb, had been covered by earth. The diagonal stones pointing outward, once held the edge of the mound. And yet, you could see it at once as the framework of an underground burial space and as a structure or a sculpture: a set of stones on the land.

Like the people before us, we went into it, onto it, photographed it. The wind blew through the trees above and the light kept changing. Molly climbed onto it. In a field just beyond this patch of woods, two brown mares and their foals grazed, their tails swishing at flies.

A few days later, leaving Brittany, we drove through the Paimpont forest near Rennes and looked for the place known as "le Tombeau de Merlin" (Merlin's tomb) in one of the places that has been identified as the Arthurian woods of Brocéliande. The tourist information center in Paimpont provided a map. From the mob in the gift shop, the animé pixies and gnomes on its walls, and the cutesy names of the surrounding streets, it was pretty clear that the area was being marketed to families as a kind of themed landscape of magic. We drove off through the very beautiful forest to find it all the same, following signs that led to a congested parking lot and well-worn walking paths.

A sign at the entry explained that "le tombeau de Merlin" had been a Neolithic site (another covered passage tomb) that had been "discovered" in 1820 by the amateur antiquarian Jean Côme Damien Poignand who was responsible for locating much of the Arthurian legends, in the Paimpont forest. As Michel Calvez writes, this landscape is today a crystallization of the meanings imposed upon it in the 19th century. In short, Poignand made it up. He located many of the events of the Knights of the Round Table in the immediate landscape so that one may visit Merlin's tomb, Viviane's tomb, The Valley of No Return, The tomb of the Giant, The fountain of Jouvence, and the pavilion of Morgane in one convenient park.

A sign at the entry explained that "le tombeau de Merlin" had been a Neolithic site (another covered passage tomb) that had been "discovered" in 1820 by the amateur antiquarian Jean Côme Damien Poignand who was responsible for locating much of the Arthurian legends, in the Paimpont forest. As Michel Calvez writes, this landscape is today a crystallization of the meanings imposed upon it in the 19th century. In short, Poignand made it up. He located many of the events of the Knights of the Round Table in the immediate landscape so that one may visit Merlin's tomb, Viviane's tomb, The Valley of No Return, The tomb of the Giant, The fountain of Jouvence, and the pavilion of Morgane in one convenient park.

|

| Jean Côme Damien POIGNAND, Antiquités historiques et monumentales de Montfort à Corseul par Dinan et au retour par Jugon, Rennes, Duchesne, 1820, 140-141 — |

Poignand wasn't acting alone. In 1824, François Blanchard de la Musse confirmed the identity of the Neolithic monument as Merlin's tomb. Many antiquarians and historians of the early 19th century attributed Brittany’s Neolithic stone monuments (c. 5200-2200 BC) to the Celts and Druids who settled in Brittany at least one thousand years later. Writers, artists and illustrators followed this romantic, nationalist interpretation of Neolithic monuments as Celtic ruins: like the Ossian hoax, they were considered a testimony to a native tradition of Northern France that was resistant to the Roman Empire and had no ties to Mediterranean classicism.

Although there were no published works on Brittany’s prehistoric stones before 1760, by the mid 19th century, menhirs, dolmens, and the Carnac alignments were one of the most common themes of landscape description. Republican historian Jules Michelet comments in 1851 that it is unlikely to walk a half hour in some parts of Brittany, “without encountering one of the formless monuments that are call druidic." Claiming Merlin for Brittany, Jacques Cambry (1795) and Miorcec de Kerdanet (1818) proposed that he had been born on the Isle de Sein. Locating his tomb in Paimpont helped to further resolve his history, as historian Marcel Calvez argues.

Mad about the Arthurian legends, over the course of the 19th century, many French folklorists and antiquarians joined in the search for the sites of Brocéliande, adding layers of myth and speculation to the sites of Paimpont forest.

Archaeologist Felix Bellamy(1896) drew up an inventory of these, rejecting some theories and establishing a map of legends and definitive histories (Calvez). Tourist maps and itineraries of the forest (like those drawn up for Fontainebleau) arrived as early as 1860.

In 1889, the archaeologist Felix Bellamy described the Neolithic monument as “a covered walkway of which only six stones remained.” A similar covered alley, that he proposed as Arthur's tomb, is illustrated in his book, La forêt de Bréchéliant, la fontaine de Bérenton (1896, volume 1). In 1892, treasure-hunters, persuaded that treasure lay buried beneath the great stones, blew up the Neolithic tomb. Two disappointing, fragmentary stones are all that remain.

To return to our visit last week: Molly circled the stones, barefoot, hoping to find something of her beloved Merlin there. The sad, bedraggled stones didn't give anything back. The dirt of the crowded clearing around them was thick with ugly wood chips and the stones were hard to see as they were so draped with stuff that many visitors had left-- bits of fern, stones, and sticks.

|

| The first published image of "Merlin's Tomb," Magasin Pittoresque, 1846 |

Although there were no published works on Brittany’s prehistoric stones before 1760, by the mid 19th century, menhirs, dolmens, and the Carnac alignments were one of the most common themes of landscape description. Republican historian Jules Michelet comments in 1851 that it is unlikely to walk a half hour in some parts of Brittany, “without encountering one of the formless monuments that are call druidic." Claiming Merlin for Brittany, Jacques Cambry (1795) and Miorcec de Kerdanet (1818) proposed that he had been born on the Isle de Sein. Locating his tomb in Paimpont helped to further resolve his history, as historian Marcel Calvez argues.

|

| Julia Margaret Cameron, Vivian and Merlin, c. 1876 |

|

| Gustave Doré,Vivian and Merlin, c. 1867 Bourg-en-Bresse. |

Archaeologist Felix Bellamy(1896) drew up an inventory of these, rejecting some theories and establishing a map of legends and definitive histories (Calvez). Tourist maps and itineraries of the forest (like those drawn up for Fontainebleau) arrived as early as 1860.

| |

| Source: bnf exhibition on King Arthur, http://expositions.bnf.fr/arthur/it/102/02.htm |

|

| Topography of the Forest of Brocéliande by Abbot Gillard (1953). As published in Marcel Calvez (2010). |

In 1889, the archaeologist Felix Bellamy described the Neolithic monument as “a covered walkway of which only six stones remained.” A similar covered alley, that he proposed as Arthur's tomb, is illustrated in his book, La forêt de Bréchéliant, la fontaine de Bérenton (1896, volume 1). In 1892, treasure-hunters, persuaded that treasure lay buried beneath the great stones, blew up the Neolithic tomb. Two disappointing, fragmentary stones are all that remain.

| |||

| |

To return to our visit last week: Molly circled the stones, barefoot, hoping to find something of her beloved Merlin there. The sad, bedraggled stones didn't give anything back. The dirt of the crowded clearing around them was thick with ugly wood chips and the stones were hard to see as they were so draped with stuff that many visitors had left-- bits of fern, stones, and sticks.

Sources/ Further reading:

Félix Bellamy, “La forêt de Bréchéliant : la fontaine de Bérenton, quelques lieux d'alentour, les principaux personnages qui s'y rapportent : tome premier / Félix Bellamy,” Collections numérisées - Université de Rennes 2, consulté le 11 août 2016, http://bibnum.univ-rennes2.fr/viewer/show/561#page/61/mode/1up Voir en ligne. pages 210

Marcel Calvez "Brocéliande et ses paysages légendaires" Ethnologie française, T. 19, No. 3, Crise du paysage? (Juillet-Septembre 1989), pp. 215-226

Marcel Calvez. Druides, fées et chevaliers dans la forêt de Broc eliande : De l'invention de la topographie légendaire de la forêt de Paimpont a ses recompositions contemporaines.. Festival

international de géographie. Programme scientique, Oct 2010, Saint-Die-des-Vosges, France.

<halshs-00525461>

Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué, « Visite au tombeau de Merlin » dans Revue de Paris, deuxième série, 1837, XLI, p. 45-62.

Jean Côme Damien Poignand, Antiquités Historiques Et Monumentales À Visiter De Montfort À Corseul, Par Dinan, Et Au Retour, Par Jugon, Avec Addition Des Antiquités De Saint-Malo Et De Dol, Étymologies Et Anecdotes Relatives À Chaque Objet. Rennes: Duchesne, 1820. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=pcd_luemTdkC

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tombeau_de_Merlin

http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/theme/broceliande

http://www.paysdebroceliande.com/broualan/broceliande-paimpont.html

CHARTON, Edouard, « Le tombeau de Merlin », Le Magasin Pittoresque, Vol. 14, 1846, p. 87-88, Voir en ligne. pages 87-88.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)