The new satellite Louvre in Lens France (a town notorious for the unrivaled height of its coal slag heaps) is a remarkable case of a museum design in a dialogue with its site. This and other photos come from my visit in December, 2013, about a year after it opened. Lens is a small city in the Nord-Pas de Calais region of northern France, a half-hour's drive from the vibrant city of Lille, and near the Belgian border. It is a place that has been repeatedly destroyed-- by coal mining, both World Wars, Nazi occupation, large-scale mining diasters, and post-industrial unemployment. Ever since the Guggenheim built its satellite museum in Bilbao, art museums have been inaugurated in depressed areas (depopulated city centers, former factory sites, etc.) to foster economic development. Lens certainly meets this criteria, and adds to it a landscape in ecological ruin.

The mining site that the new museum occupies was a working site until 1960. There was coal mining in the area until 1986.

|

| Early 20th century post card showing Pit #9 in Lens |

|

| The Slag Heaps of Lens in the 1930s |

|

| Lens Before and After the First World War |

|

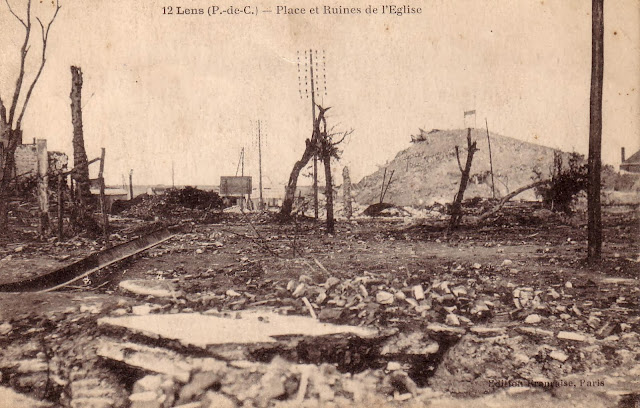

| Ruins of a church in Lens |

|

| German Pillbox near Lens. Canadian troops inspect a captured German gun position near Lens, France in September 1917. |

I had read about the open-plan of the great hall in the museum, and was intrigued by the imposed constrains of the silver walls (more on this below) but I was unprepared for the affective qualities of the museum's landscape design.

The concrete seems only a fragile and partial covering (something here for now) on this site. Like new skin slowly covering a healing wound, the flat areas of the concrete have gaps that seem to reference deep craters in this landscape that cannot simply be filled in and forgotten. But today the dirt mounds up where it can, exploding with verdant life.

In this region, it rains a lot in the winter, deepening the color of the dark soil and the emerald life coming from it. Water seemed to be almost weeping up from the saturated soil on the morning we arrived. As the fog cleared and the sun came out, the water retreated.

In this photo below, from 2012, it appears that the gaps had been planted last year. There was something much more vulnerable about seeing the dirt exposed.

|

| December 2012, just before the museum opened you can see the careful plantings that filled the openings in the concrete. This is not one of my photographs-- it is a promotional image from that time. |

The site had become overgrown after being closed in 1960. These trees (below), sprouting from the former mine shaft, seem to have grown since then. They attest to the vitality of the land, as do many of the tree-covered slag heaps we passed in the region, their winter skeletons revealing the perfectly cone-shaped hills beneath them. This ruined land was once fertile (like most of the contested front) and it is green despite it all. My previous work on quarries, wasted space, entropy and land art came to mind immediately. This was a work of land art, an "ecovention" that reused and reframed a previous ecological mess.

|

| The former entrance to the mine shaft is marked and preserved here, making clear what has been filled in. |

|

| Post card showing debris filling the mine shaft after the War. |

|

| The round shapes break into straight lines in the concrete. |

In the "Galerie du Temps," chronology rules the order of things: a timeline of five millenia etched on one aluminum wall orients the viewer as she chooses a path through the 32,000-square-foot space. Twenty percent of the collection moves in or out each year-- thus a return visit in five years guarantees a completely refreshed collection.

The works are well labeled and there are the audio guides for those who want them.

|

| http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/composite-female-statuette |

Paintings are things too.... they have three dimensionality, weight and texture.

All art objects are things. All need support, protection. In this open room, dialogues are infinite, pathways are not proscribed.

Chronology is the organizing tool, yet the viewer's movement rarely follows a strict historical march.

We end in the mid 19th- century, as in the Louvre-Paris. This wonderful Barye bronze seems more animated than ever before in such a vibrant space.

This is a reflective space (sorry about the pun but bear with me). The reflective aluminum walls that cannot have work hung upon them direct the focus inward inside, to almost vanish outside. Outside, the aluminum walls almost vanish in the landscape, and the glass walls encourage repeated reflection on the site.

Links: DE ZEEN review

Detail review

Interview:

And an unrelated story about a Chinese hotel being built in a quarry [!]

No comments:

Post a Comment